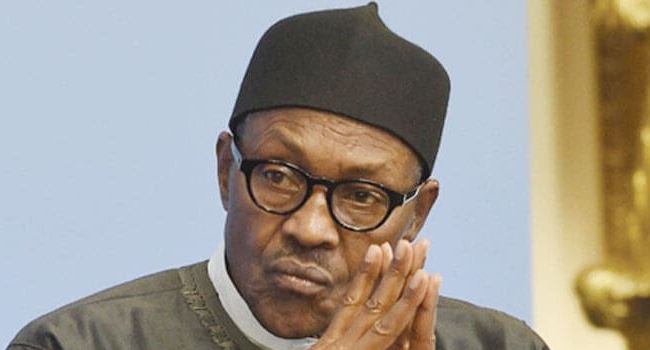

When Nigeria goes to vote in presidential elections on February 25, 2023, it will be the first presidential election in 20 years in which Muhammadu Buhari will not be on the ballot. He will be term-limited having served the constitutionally permissible two terms following three previous unsuccessful attempts from 2003 to 2011.

The nomination conventions of Nigeria’s leading political parties have now concluded with clarity as to who will compete to become Nigeria’s 16th head of state in succession to Muhammadu Buhari. Against former Vice-President Atiku Abubakar of the Peoples’ Democratic Party (PDP), the ruling All Progressives Congress (APC) will field former governor of Lagos state, Bola Ahmed Tinubu. They will be the two leading candidates.

Azubike Ishiekwene has described the story of the choice of the candidate of the APC as a chronicle of Muhammadu Buhari’s mastery of “strategic ambivalence”. There is little evidence to support the existence of any such strategic wizardry.

The day before the scheduled beginning of the convention, 11 governors of states in northern Nigeria all on the platform of the APC issued a common position affirming that “the search for a successor as the APC’s presidential candidate be limited to our compatriots from the southern states”. In the same statement, they appealed to “all aspirants from the northern states to withdraw in the national interest and allow only the aspirants from the south to proceed to the primaries”. This was a big deal because the governors collectively determine who wins the party’s nomination for the presidency through their control of the delegates from their various states.

Of the 23 aspirants seeking the nomination of the ruling party for the position of president, only Abubakar Badaru (Jigawa); Yahaya Bello (Kogi); Ahmad Lawan (Yobe); and Sani Yerima (Zamfara) were from the north.

Moments after this statement was issued, reports filtered out that President Buhari had also endorsed the position of the northern governors. This seemed a logical next step after the president informed his party the previous week that he desired to be accorded the privilege of designating his successor to lead the party into next year’s polls. There was one important point of difference between the northern governors’ position and that of the president; while the governors urged all northern aspirants to abandon their ambitions and step down, the president chose to be silent on that.

Rather bizarrely, after informing the party of his desire to anoint a candidate to succeed him, President Buhari hopped on the presidential jet and promptly flew off to Ibiza for three days. Returning from Spain a mere three days before the convention, the president jetted off again to Ghana. He could not spare the time or attention needed to bring about the outcome he desired. There was no strategic genius in that. Rather he stoked a political vacuum which the northern governors were only too happy to seize.

Contemporaneously with his reported endorsement of the rotation of power to the south, the Vanguard newspaper reported a claim by senior northern politician and former Nigerian foreign minister, Sule Lamido, that President Buhari was privy to a scheme that would lead to the emergence of the senate president, Ahmad Lawan and former transportation minister, Rotimi Amaechi, as the presidential ticket of the APC. This seemed odd because Lawan, contrary to this position, is from the north.

On the same day, Lawan paid a high-profile visit to another of the APC’s presidential aspirants and Ebonyi state governor, David Umahi, after which they were reported to have struck a mutual support deal in the race for the party’s ticket. At this time, in the light of the announcement by the northern governors, Lawan should have been tendering his withdrawal from the race not picking up endorsements from fellow contestants. It should have been evident that in politics there is no coincidence.

Early afternoon the following day, on Monday, June 6, party chairman, Adamu Abdullahi, reportedly announced to a stunned national working committee (NWC) of the APC that their consensus presidential candidate will be Lawan and all hell seemed to break loose. First, the 11 northern governors swiftly pushed back against this announcement, reaffirming their position about the ticket shifting to the south. Next, a significant member of the NWC disowned the announcement, saying it did not come from them. Quickly, on the president’s behalf, a statement was scrambled to say that he had no preferred candidate and claimed that he was determined to see that there was no imposition of any candidate on the party.

Notably, Garba Shehu, the spare presidential spokesperson who issued this statement, was not present at the frenzied consultations among party leaders on the subject matter. The statement also explicitly contradicted the position, first announced by the president in a high-profile interview in January 2022, that he had a preferred successor. It was difficult to know what to believe – the statement issued on behalf of the president or the very words that he uttered himself. In the end, the world waited in vain for Buhari to unveil his successor or to marshall his plan behind such a person.

None of this reveals any mastery of strategic ambivalence. Instead, the journey to the APC convention produced the kind of orchestrated confusion that has characterized the past seven years of this second Buhari misadventure. Not for the first time in Nigeria’s contemporary history of political transition, a president with military provenance appeared to lose his nerve when he needed to keep it.

It seems inconceivable that Abdullahi Adamu, a veteran politician who had served eight years as state governor and two terms in the senate before becoming party chairman this year installed single-handedly at the say-so of Mr President, would have gone rogue to all by himself designate a “consensus” nominee without the knowledge or approval or the president. Indeed, the mere suggestion of the idea that he did not know damages Buhari much more than an acknowledgement that he did.

It seems more plausible that what happened was that the president, having authorized or requested Adamu to issue the announcement, promptly threw him under the bus when it became evident that he had probably under-estimated the blow-back that followed. Such a scheme would be entirely in keeping with the narrow, nepotic outlook that has defined the Buhari years. A look at the underlying fundamentals of the Nigerian trajectory makes clear the logic that may feed a reluctance on the part of the north in the APC to yield up power.

Violence has destroyed social capital, enterprise and innovation in the region that has produced most of Nigeria’s leadership, to the point where its elite sees their own survival only in terms of seizing power at the centre from where they can redistribute revenue obtained mostly from the south in order to buy off or postpone more violence from an impoverished underclass. But to sustain this would require an internal colonial arrangement that could imperil the Nigerian enterprise beyond a point of no return.

The alternative to gaslighting the country in this way was to gaslight the party. The consequence was a nasty demolition derby of a party primary whose outcome was settled in favour of the only bidder who could afford the bullion vans to buy the entire delegate value chain from the political factory through wholesale and logistics to retail. As the ruling party’s convention began in Abuja, all foreign currency notes in the federal capital dried up in both the banks and the Bureaux de change, ending up in the hotel rooms and wallets of the party managers and delegates.

The competitors included “a sitting vice president, a serving senate president, five current governors, five ex-governors, an-ex senate president,” and four ex-ministers. In the event, Buhari was forced by his own cynical ineptitude to become a spectator in the theatre of his own succession within the party. He did not evince a legacy worth fighting for.

The result was a hostile takeover of the party by a co-founder driven to extreme distraction at his own exclusion from the fortunes of the party he built. There will be time to assess the landscape of the ensuing contest but what emerges is clear. The two biggest parties have split along regional lines with the emergence of Rabiu Kwankwaso’s New Nigeria Peoples Party (NNPP) in the north-west and Peter Obi’s Labour Party (LP) platform in the south-east. They could become kingmakers.

This lineup guarantees that General Buhari, the man who promised improved security and coexistence in 2015, will be leading Nigeria into perhaps its first centrifugal elections since independence. It is a sad commentary on this Buhari misadventure that the contest to replace him may become one in which the country will be voting on whether or not to stay together.

Chidi Anselm Odinkalu